![]()

![]()

In the [Duke] Ellington conception [of composition], it isn’t the instrument that’s being played that makes the difference but the man who plays it. The leader of our next group has found himself in the same situation, which Mr. Ellington has known, that of establishing a very distinctive, original, personal sound and then hearing it coming back from all of his admirers and being forced to extended his own creative boundaries once again to find something that is, again, distinctively his own (Connover).

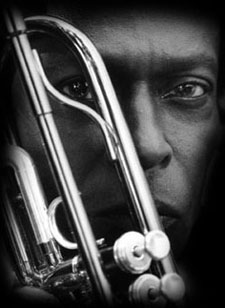

This is the introduction that Miles Davis received at the 1958 Newport Jazz Festival. At this time, the man had already changed his personal style and the course of jazz music at least twice, and he was on the precipice of another great change. After this speech, Davis would continue to evolve and change for thirty-three more years, and he would influence countless musicians and non-musicians alike. During these years he shifted musical tracks countless times in an effort to find his own sound. From bebop, to cool, to hard bop, to orchestral, to modal, to fusion, and beyond, Miles never let himself stay in one place musically for too long. His drive to change came from his deep love for his father and his need to prove his ability as a musician and black man in the turbulent times in which he lived. Miles Davis reinvented his music and image many times in his illustrious career, especially prior to 1970.

Miles Dewey Davis III was born to Miles Dewey Davis II and Cleota Henry Davis on May 28, 1926. The family lived in Alton, Illinois, but moved to neighboring East St. Louis within the year. The family had a fairly high standing in the community, his father being a dentist educated at Northwestern College. Miles’ father had a strong influence on the course of Miles’ life (Carr 1-2).

Miles II made his children (Miles had an older sister, Dorothy, and younger brother, Vernon) aware of their race from a young age. Though they were an affluent family, the Davises were subject to racism. Miles’ father was a fan of civil rights advocate Marcus Garvey and would risk his own safety to advance the social standing of his race. Miles always had a great deal of respect for his father, and his words would greatly affect Miles’ future choices. It was he who told Miles to always be an individual. After his father’s death, Miles said, “I knew I had a great father. I mean a great one” (Davis 22-28, 74, 258).

It was Miles’ mother, though, who would have the earliest musical influences on the boy. She grew up in the South and played violin and piano. Her southern heritage formed her and Miles’ musical tastes. When she would send the children to her parents’ farm in Arkansas, Miles heard the sounds of blues and gospel (Carr 3). He would recall this later when he took up music (Davis 28). She also gave him two jazz records; one by Duke Ellington and the other by stride pianist Art Tatum. The gift that would have the most profound effect on Davis, however, came from outside the family (Carr 3).

At about the age of nine, Miles received a trumpet from an associate of his father, Dr. John Eubanks (Carr 4). Elwood Buchanan was a drinking buddy of Miles’ dad and also the band director at the local high school. Mr. Buchanan agreed to give the young boy lessons on his new instrument (Davis 30). Miles had also begun listening to the “Harlem Rhythms” radio program before school (Carr 4). These two experiences resulted in Miles being completely captivated by music by the age of twelve (Davis 30).

When Miles entered Lincoln Senior High School, he was in love with music (Miles Davis Story). He also made a valuable friend during this time. Clark Terry was a famous jazz trumpeter in the St. Louis area and a friend of Elwood Buchanan (Carr 7). Terry acted as a mentor to the fledgling musician and introduced Davis to the local jazz scene (Davis 33, 44). Exposure to the professional player, continued lessons with Mr. Buchanan, and, later, with a teacher and expert mouthpiece maker known only as Gustav, allowed Miles’ skill to increase rapidly. He joined the musicians’ union at 16, and by the time he graduated in 1944, he was making a good living playing with local groups (Carr 9-11).

Miles decided to go to New York after graduation, ostensibly to study at Juilliard, the prestigious school of music. He would spend his days practicing music and his nights searching for the great alto saxophonist Charlie “Bird” Parker (Carr 18–20). Parker, along with trumpeter Dizzy Gillespie, was the main force and innovator in the bebop movement of jazz. Of the two it was Gillespie who taught Miles the most in terms of theory (Davis 68).

Through Parker, Miles became a member of the “hip” crowd of musicians on 52nd Street. He would play and talk with great jazz musicians, like Bird, Dizzy, and pianist/composers Thelonius Monk and Tadd Dameron. The latter three would often write out chords, which he would practice during the day while at Juilliard. Miles spent a lot of time in the practice rooms because he did not care for the school’s curriculum, though he did take symphonic lessons and some piano courses. Miles dropped out of Juilliard in the fall of 1945 (Carr 20-23).

Davis was now free to completely engross himself in the bebop scene. His lucky break would come only a few months later (Davis 68). Bird was notorious for his heroin addiction, and by 1946 the twenty-five year old saxophonist had been using for almost eight years (Jazz). His clean-living companion, Gillespie, grew increasingly upset with Bird’s lack of professionalism and left their group. Parker picked Miles as Dizzy’s replacement. Davis was apprehensive, though, because he and Dizzy had very different styles, but this fact ended up helping the young trumpeter in the long run. In Parker’s group Miles realized that he could not copy Gillespie; he just had to play in his own way (Davis 68-69). In 1946 Bird was at his musical pinnacle, and Miles was living the dream all jazz musicians at the time (Jazz). This collaboration would last almost three years (Carr 40).

During his time in the band, Miles was influenced by Bird in several ways, both positive and negative. Like Miles in the future, Parker would rarely make announcements to the crowd and allowed the musicians to play freely, giving few instructions (Carr 41). He also had a habit of not showing his musicians new music until the day of a recording session. In doing this Parker captured the group’s freshest interpretation of the music on the record. The influence of hearing Parker’s passionate, inventive solos every night also cannot be underestimated. Despite these invaluable lessons, this group would also lead Miles into one of his darkest periods because it was here that he began using cocaine and experimented with heroin (Carr 41, 34).

After his departure from Bird’s group in late 1948, Miles renewed a friendship with pianist/arranger Gil Evans that had begun a year earlier. Evans was a self-taught musician who was working as an arranger for Claude Thornhill (Carr 40, 45-46). Gil was also spending a lot of time with young New York musicians who enjoyed hanging out in Evans’ basement apartment. Among these were baritone saxophonist Gerry Mulligan, altoist Lee Konitz, and Miles. Miles, Gil, and Gerry found themselves searching for a softer sound than bebop was offering. Gil was very qualified for this job. He was very interested in classical composition and was bringing this into his arrangements for Thornhill, using non-jazz instruments like French horn and tuba. The three formed an unconventional nine-piece band. The group included Lee Konitz, a jazz rhythm section, a French horn, and a tuba (Carr 46, 49). Unfortunately, the public did not understand the odd music. The group played only two club engagements and a few radio broadcasts. The group also recorded several pieces for the Capitol record label. These would be released by Capitol in 1957 on an album entitled Birth of the Cool. It was this record that would later win critical acclaim for the use of light, melodic arrangements that contained fairly little improvisation (Carr 54-56). These sounds would come to define Miles style and tone: light, sparse, and introspective. After these few large group performances, Miles moved his music in a new direction, and all other musicians would follow (Fordham 37).

Miles was now playing in jam sessions with musicians around New York. In 1949 he took a trip with a friend, pianist Tadd Dameron, to France for the Paris Jazz Festival. He fell in love with the city and a French singer named Juliette Greco. The European audiences and critics were very receptive to his playing, and Miles would later call this one of the happiest times of his life. After only a couple of weeks, Miles left the city but was so captivated by the experience that his departure lead to a fit of depression that would cause him to rely heavily on drugs (Davis 125-127).

Miles was now playing a style of music developed by drummer Art Blakey and Horace Silver. Dubbed “hard bop” by critics, the new music was an attempt to bring black music back to the forefront of jazz, which was now dominated by “West Coast” or “cool” jazz, a form that was derived from Miles’ large group work by former colleague Gerry Mulligan along with various others. The new music combined all facets of the black musical heritage, including bebop, blues, and gospel. Unfortunately, after a few recording sessions for Bob Weinstock’s Prestige Records, Miles’ heroin addiction led to a career slump. From 1952 through most of 1953 Davis would spend time traveling the country with fellow addict drummer Philly Joe Jones. They would play with pick-up bands of local musicians. Club owners did not want to hire junkies, so Miles found it hard to find constant work and began pawning his (and others’) possessions. After several attempts by his family to clean him up, Miles realized that he had to make up his own mind to quit (Carr 63-73). He did so by locking himself in his father’s guesthouse for over a week (Davis 169-170). He was in terrible pain but found the strength inside to quit, saying to himself, “The next hour is gonna be better. The next minute is gonna be better” (Miles Davis Story). Despite breaking the habit, Miles continued to use heroin off and on for the next five months. It was in his love of boxing, specifically that of the clean living, determined Sugar Ray Robinson, that gave him the strength to break free of heroin for good (Davis 174).

Now clean, Miles returned to New York in 1954 ready to play. He recorded six times that year, some featuring hard bop innovators Horace Silver and Art Blakey. Soon, he began getting a new group together. It would become his first of several memorable small ensembles he would assemble during his career. This “classic quintet” consisted of Philly Joe Jones, bassist Paul Chambers, pianist Red Garland, and future jazz legend John Coltrane (Carr 78-82, 89-93). Around this time Davis was heavily influenced by pianist Ahmad Jamal; he even chose Garland for his ability to mimic Jamal. Ahmad’s playing was light and understated, and his song selection was varied, bringing in many tunes from Broadway musicals (Davis 190, 178). The band became popular, and Miles would not let anything get in the way of his new musical vision (Carr 97).

Miles was developing a unique musical style and also a distinct personality. When John Coltrane entered the group, Miles fell in love with the man and his music, but even his phenomenal ability would not deter Miles need for perfection. When Coltrane began nodding off on stage due to his own heroin addiction, Miles could take it no longer and kicked Trane out of the group. Miles later allowed Trane to return but once again removed him due to his drug addiction. Not only was Miles a perfectionist, he was also extremely competitive as is pointed out by an incident during a stay at the Café Bohemia in 1957. Trumpeter Kenny Dorham sat in with the quintet and proceeded to upstage Miles. Miles had great respect for Dorham but also tremendous pride in himself; he left the club that night furious with himself. The next night Dorham returned, and Miles was not about to be outshone again. He dazzled the audience and played like he knew he should have all along: like Miles Davis and not like anyone else. At this point his temperament was just as fiery as his playing. He once punched bassist Paul Chambers when he refused to pay for his bar tab and even slapped his best friend John Coltrane due to his lack of professionalism (Davis 207-215). Miles would not allow his artistic vision to be compromised.

The new quintet recorded several times in 1956, including a string of four albums recorded in two sessions with no second takes: Workin’, Cookin’, Relaxin’, and Steamin’. These albums were made to satisfy Miles’ contractual obligation to Prestige Records (Carr 97-101). He had signed a deal in 1956 to record for Columbia records when his Prestige contract ended in 1957. He felt that Columbia would allow him to reach more people (Davis 205-206). He would record his seminal album, Kind Of Blue, for Columbia two years later (Carr 144).

After several line-up changes in 1957, all of the members of the quintet returned to form a stable group, but the quintet was now a sextet with the addition of bluesy alto saxophonist Julian “Cannonball” Adderley. Late in the year they recorded the album Milestones. This album was different from Davis’ other albums because instead of songs with solos based around complex chord changes, like most hard bop songs, this album contained one song, “Milestones,” based on specific scales, or modes (Carr 121-122, 127-130). Soon after this recording, though, tension in the band grew.

Philly Joe and Red Garland were heroin addicts. They began missing gigs, so Miles decided to replace them. Philly Joe was replaced with Jimmy Cobb, who had filled in for Joe several times already. To fill the role of pianist, Miles brought in a white musician named Bill Evans. Evans left to form his own group in the fall of 1958, after only seven months with the group. He was replaced by a black man, Wynton Kelly (Davis 229, 225-226). This was not the last time Evans would play with the group.

On March 2, 1959 Miles met with Evans in the recording studio again to create an album that would change jazz forever, Kind Of Blue. Miles, with the aid of Evans, wrote all original material for the date. These tunes expanded on Miles’ previous attempts at “modal music,” songs based on scales instead of chord changes. The group recorded three songs at this session and two more at a session on April 22. Except for “Flamenco Sketches,” all songs on the album were the first complete take of the piece. This is a marvel of skill and musicianship. The album’s simple elegance, soft style, inventive composition, and marvelous playing made it Miles’ best selling of his stellar career, and possibly the most influential jazz album ever (Kahn 88, 95, 102-117, 124, 133-142, 177-182, 195).

During the time of these stunning sextet recordings, Miles also worked with his old friend Gil Evans. Miles used the immense recording budget that Columbia offered to make records that featured larger ensembles. Their first Columbia collaboration, Miles Ahead, featured Miles on flügelhorn backed by an eighteen-piece orchestra. This record, released in 1957, was lighter and softer than Miles’ quintet work of the time and produced a nice backdrop to showcase Miles’ singing tone. The following year the duo made an album of songs from the Gershwin opera Porgy and Bess. Miles called this “the hardest record I ever made.” Miles and Gil would pair up once more to make what would become Miles final album of the 1950’s (Carr 109-113, 139, 141, 158). Inspired by a recording of Concerto de Aranjuez by Joaquin Rodrigo, Miles decided to create an album of flamenco music (Davis 241). This proved to be a challenge, taking an unprecedented fifteen three-hour sessions to record, but the work paid off and the pair created a masterpiece (Carr 158). They would come together again to create an album of bossa nova music, but the idea did not work out. Columbia released the music against Miles’ wishes in 1962 under the title Quiet Nights. Evans, however, was a positive influence on Davis. The two had very similar ideas on music, and Evans was able to push and motivate Miles (Davis 259, 184). Though Miles had created another unique sound, he was about to change music again.

In the spring of 1960 the sextet was beginning to fall apart. Miles choice of the top musicians of the day ended up being its undoing. The members began feeling a need to leave and start their own groups. Adderley had left the group in September of the previous year, and John Coltrane was preparing to start his own group. The rhythm section of Kelly, Cobb, and Chambers followed and became the Wynton Kelly Trio (Carr 145, 168, 185). Miles now needed to form a completely new group. After numerous line-up changes, Miles finally got a steady group together (Davis 261-263). The rhythm section of this group consisted of Herbie Hancock on piano, Ron Carter on bass, and seventeen year old Tony Williams on drums. They have been called the greatest rhythm section ever due to their elastic feeling of time and harmonic genius. They freed themselves completely of chord changes.

It seems odd that Miles would choose to go the direction of “free jazz.” This was a style pioneered by altoist Ornette Coleman that shed the music of all chords, forcing the soloist and rhythm section to use their ears to find pitches that sounded good, giving everyone more freedom and bringing the sounds of squeaks, squawks, and screeches into the Jazz vocabulary (Fordham 42-43). Miles did not like this avant-garde music and was vocal about it, having a particular resentment toward tenor saxophonist Archie Schepp (Carr 215). The reason Miles quit using chords was due to a slightly different approach. His new saxophonist, Wayne Shorter, began doing most of the writing for the group. Unlike the free jazzmen, Shorter’s tunes did not get rid of form; instead he attempt to make radical changes to the form. Nonetheless, Miles and the group were now playing free solos lacking standard harmonic boundaries and playing off Tony Williams’ innovative drumming (Davis 271-278). Miles allowed the group to perfect this style, waiting two years before making their first studio recording, entitled E.S.P. (Carr 201). The second “classic quintet” would record several more albums, including Miles Smiles, but it would, like the previous groups, eventually dissolve (Carr 227-229, 212).

Miles’ new group was set by 1969; it contained the white British bassist Dave Holland, pianist Chick Corea, and drummer Jack DeJohnette. During this time Corea began experimenting with a Fender Rhodes electric piano and other electric instruments. Miles soon started to incorporate more and more electronics (Miles Davis Story). In February of that year Miles recorded a dramatically new album. The album was called In A Silent Way and featured three electric pianists: Corea, Hancock, and former Cannonball Adderley organist Josef Zawinul. It also featured the British electric guitarist John McLaughlin. The recording session was almost completely improvised and spanned two hours. This was cut down to just nine minutes that were intricately edited and repeated to form an entire album (Carr 244-250). This album led Miles into more rock based, or “fusion” music. This transformation would be made complete with his album Bitches Brew. From then on Miles’ group would undergo many changes, but the basic rock and funk beats would remain. His frantic pace of change that had lasted more than two decades slowed due to increased pain from sickle-cell anemia and cocaine addiction. Miles died of a stroke in 1991, but his music and influence remain (Miles Davis Story).

Miles has received mixed evaluations throughout his career. He has been accused of being hostile toward audiences: turning his back on them, leaving the stage, and not acknowledging his listeners’ applause (Miles Davis Story). He was also accused of being racist towards whites. Miles did do these things, but he did them out of respect for his music. He was always trying to make a statement, often one about his race. He did not want to be like some black artists, particularly Louis Armstrong and Dizzy Gillespie, who he thought were trying to impress white people. He wanted people to come to hear his music, not just to see Miles Davis (Davis 248, 83, 163). In this way Miles became a symbol of power for blacks. Not only did he inspire members of his race, Miles also received unprecedented acclaim from critics. He won more than twenty of the prestigious Down Beat magazine readers’ polls and also won awards from various other jazz magazines from around the globe, like Metronome, Jazz Echo, and Muziek Espress (Carr 32, 40, 88, 114, 134,162, 168-169, 183, 203, 270, 301, 345, 383). He also won eleven Grammy’s (“Awards of Miles Davis”). His biggest influence, though, can be heard in the music that followed his entrance to the jazz scene. Miles introduced a simple style. He wanted to find the right note to play at the right time, and he was not interested in the fast lines of the beboppers. He thought most musicians played too much (Davis 70, 219-220). His good friend Gil Evans even said during an interview that Miles has become the major influence in jazz trumpet, replacing Louis Armstrong (The Miles Davis Story). To be seated this highly in the jazz world, Miles’ impact cannot be underestimated.

During a 1986 recording session for the star-filled protest song “Sun City,” Miles was approached by guitarist Bonnie Rait. A clearly honored Rait told the trumpeter he “sounded great.” Miles coolly leaned back, stroked back his now receding hairline, and said in his low, raspy whisper, “Thanks, that's my thing” (The Miles Davis Story). And that thing made Miles Dewey Davis III one of the most famous and innovative figures in musis for more than four-decades. He has been called the “Picasso of Jazz,” and, like the painter, Miles never let his music fall into a rut of sameness (“Cool is Forever”). He was a genius of music and his changing styles led to his influence extending not just beyond jazz but also beyond music into all of contemporary culture.

WORKS CITED

“Awards of Miles Davis.” 123 Awards. 16 Oct. 2004 <http://www.123awards.com/Artist/2322.asp>

Carr, Ian. Miles Davis: The Definitive Biography. Great Britain: Thunder’s Mouth Press, 1998.

Connover, Willis. Introduction By Willis Connover. With Miles Davis, Cannonball Adderley, and John Coltrane. Columbia/Legacy, CK 85202 3 July 1958.

“Cool is Forever.” Miles Davis. 2002. Sony Music Entertainment. 25 Oct. 2004. <http//:miles-davis.com>.

Davis, Miles & Quincy Troupe. Miles: The Autobiography. New York: Touchstone, 1989.

Fordham, John. Jazz. New York: Barnes & Noble, Inc., 1999.

Kahn, Ashley. Kind Of Blue: The Making Of The Miles Davis Masterpiece. New York: Da Capo Press, 2000.

Miles Davis Story, The. DVD. Dir./Narr. Mike Debb. Columbia Music Video/Legacy, 2001. 125 min.