![]()

![]()

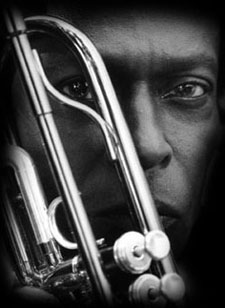

Miles Ahead

This is an extraordinarily well done album with absolutely no point at which you can wish for more. Miles' use of the flugelhorn on this album does not in the slightest detract from his communication. Rather, it lends a certain spice to it, as he extracts from this sometimes blatant instrument all its mellowness and fullness. There is no piano, but this is not noticeable at all because what occurs here is a remarkably flexible set of scores, written with a suppleness, fluidity and skill that should immediately bring Gil Evans to the front rank of contemporary jazz writers.

- Ralph Gleason; Downbeat; Dec. 12, 1957

Milestones

Rating: 4 out of 5 stars

Although Davis has not been known as one of the happy extroverts of jazz, he has quietly, deliberately, and judiciously matured as an artist. Compelled by a desire to express himself fully, he seldom has remained static. He has not wandered aimlessly, either. He has progressed along a well-defined path, assimilating wisely along the way, setting his own goals rather than gripping those of his contemporaries. While this alienated some jazzmen and listeners, more obviously so in recent years, Davis has managed to maintain his integrity without sacrificing his inherent artistry.

These comments preface any evaluation of this, Davis' latest sextet LP. It is not a wholly successful venture, primarily because Davis' companions here are not yet of his stature, although several of them may well find places in jazz comparable to his in time.

[John] Coltrane and [Cannonball] Adderley are ambitious, able jazzmen. Here, however, are primarily concerned with rhythmic exploitation, at times at the expense of communication. This is particularly evident on the frenetic Dr. Jekyll and on Monk's Straight, No Chaser, on which both men flurry excitedly flanking a splendidly structured Davis solo. On Milestones, there is inspiring compatibility. Miles sits on [Two] Bass Hit; Billy [Boy] is a trio track, with [Red] Garland given an opportunity to display his lyric side and [Paul] Chambers ably offering an acro solo.

The key track, and lengthiest, is [Sid's] Ahead, which manifests several of the characteristics of the blowing session, on a familiar theme. Davis is the leader, in every sense, playing with force a significance. Coltrane solos authoritatively, too. Chambers solos effectively. Adderley's solo is more an indication of eager groping than a cohesive statement.

The rhythm section is superb throughout.

Davis' statements here are genuinely eloquent. Although I feel that Coltrane often records material best left in the practice room, his efforts here do indicate that he is rapidly moving toward a niche of his own, absorbing influences but not being obsessed by them. Adderley is less the individualist but is performing on a level of fluency which will make the discovery of a self-sustaining role less difficult in time. Here, the three horns and stimulating rhythm section work together well, in terms of the levels noted.

- D.G; Downbeat; Nov. 27, 1958

Kind of Blue

Rating: 5 out of 5 stars

This is a remarkable album. Using very simple but effective devices, Miles has constructed an album of extreme beauty and sensitivity. This is not to say that this LP is a simple one—far from it. What is remarkable is that the men have done so much with the stark, skeletal material.

All the compositions bear the mark of the Impressionists and touches of Bela Bartok. For example, So What? is built on two scales, which sound somewhat like the Hungarian minor, giving the performance a Middle Eastern flavor; Flamenco [Sketches] and All Blues reflect a strong Ravel influence.

[All Blues] and [Freddie] Freeloader are both blues, but each is of a different mood and conception: [All Blues] is in 6/8, which achieves a rolling, highly charged effect, while Freeloader is more in the conventional blues may account partly for the difference between the two.

Miles' playing throughout the album is poignant, sensitive, and, at times, almost morose; his linear concept never falters. Coltrane has some interesting solos; his angry solo on Freeloader is in marked contrast to his lyrical romanticism on [Flamenco Sketches]. Cannonball seems to be under wraps on all the tracks except Freeloader when his irrepressible joie de vivre bubbles forth. Chambers, Evans, and Cobb provide a solid, sympathetic backdrop for the horns.

This is the soul of Miles Davis, and it's a beautiful soul.

- Downbeat; Oct. 1, 1959

Miles Davis & the Modern Jazz Giants

Rating: 4½ out of 5 stars

There are few jazzmen whose creative resources are so great that any recorded example of their work is of interest. This reissue of the 1954 and 1956 Davis sessions includes at least three such men: Milt Jackson, Thelonious Monk, and Davis himself.

The earlier date (all titles but ['Round] Midnight), which also produced Bags' Groove reveals a somewhat uncomfortable Miles, blowing with and against a free-wheeling, but only half-sympathetic, group. Davis' approach to jazz, which leans heavily upon the sensitivity of his pianist, is left tattered by the jarring individualism of pianist Monk, whose playing is not designed to flatter or inspire Miles. In spite of all this, enough memorable moments came from the session to make this a very worthwhile LP.

Swing Spring, in particular, demonstrates that Davis was ready to lead the way out of the cliché-ridden I-can-blow-stronger-you arena into which many jazzmen had stampeded by the mid-50s.

Midnight, performed by the most esthetically satisfying of all Davis groups, is a musical essay on the virtues of lyricism and horizontal structure, combined with harmonic insight, a classic performance that should be in any thoughtful collector's library.

- Downbeat; Oct. 1, 1959

Sketches Of Spain

This record is one of the most important musical triumphs that this century has yet produced. It brings together under the same aegis two realms that in the past have often worked against one another—the world of the heart and the world of the mind. What is involved here is the union of idea with emotion, precompostion with improvisation, discipline with spontaneity. Every big band chart with built-in improvised solos is an attempt at this synthesis. The real value of Sketches Of Spain lies in the fact that the intellectualism is so extreme, and at the same time, the emotional content is so profound.

- Bill Mathieu; Downbeat; Sept. 29, 1960

Four & More

Rating: 3½ out of 5 stars

The tempos are mostly the same—breakneck. Bad pacing.

Miles sounds raw, somehow unpolished. His best track is Walkin', on which he generates a good deal of heat, but they play it too fast. Miles cracks notes too often. It sounds as if he is overblowing the horn. I get chalk-on-the-blackboard-squeak chills.

[Tenor saxophonist George] Coleman runs the changes, his surface facility leading me to expect more interesting music than he comes through with.

I don't like announcements on records. It's as if they have to prove that it really was recorded live. These announcements—there is one at the conclusion of each side—give the listener all the disadvantages of being at a concert, with none of the advantages.

Davis' rhythm section cooks—the time bubbles. [Drummer Tony] Williams knows how to make clockwork interesting. His cymbal sound is crystal clear. [Bassist Ron] Carter and [Pianist Herbie] Hancock are perfect. Davis' rhythm sections always have been distinctive, setting the style for others. Williams is part Philly Joe Jones and part Milford Graves—the best parts of each, I think.

Most of my 3½ stars is for the rhythm section.

- Micheal Zwerin; Downbeat; Dec. 9, 1966

Tutu

Rating: 4out of 5 stars

Just as Gil Evans was hailed for his work on Sketches Of Spain, so should Marcus Miller be acclaimed for his work with Miles on this album. In fact, the two projects are very similar.

Now, before all you curmudgeons out there begin crying “heresy,” consider this: both projects were basically conceived by other minds and presented to Miles as a foundation on which to add his own individual voice. Both projects were intended to cross over into a more commercial market. Neither project was jazz, per se.

And not only does Marcus lay the groundwork, he plays nearly all the instruments himself as well. Basically, Tutu is the finest Marcus Miller album to date.

Side one is even a good Miles album, full of the dark, sinister, mysterious qualities that have graced his music all through the years. The brooding title cut may even satisfy old-school Miles fans, as he acquits himself beautifully on muted trumpet on a sparse, spacious arrangement. They may also accept Portia, a somber, haunting work in the tradition of Sketches Of Spain. But then in kicks the bombastic funk of Splatch, with its many sampled sounds, thumb-heavy bass line, and catchy hooks. And forget about side two. Much too poppy for anyone still stuck in a Milestones timewarp.

I'm not so hot on side two myself, but I admire Marcus' production values. The is subtle. Hear how he weaves Count Basie's voice, uttering the classic “one mo' times,” from April In Paris, into the bright fabric of Perfect Way. Not to mention all the near-subliminal pieces happening in that pop puzzle. And dig all the weird electronic dub sounds in Don't Lose Your Mind, or his clever use of clarinet to double the bassline on that tune. He make sure there's plenty happening, both in the pocket and in the fabric, before he summons the maestro to add his voice to the proceedings.

Bass players will like this album. Young fans (those who consider Bitches Brew his early period) will dig it. Prince may even groove to Full Nelson. Fellow producers will drool over this album. And big-name pop stars should take note: with Tutu, Marcus Miller may have established himself as “the new Nile Rodgers” of production.

As for Miles, who knows what might be next for the man who keeps moving? Since re-emerging onto the scene in 1981 with The Man With The Horn, his projects have been getting increasingly commercial. And yet all the while he's still playing Miles. Skeptics may dismiss Tutu as hip muzak. But if they would forget about the labels, ease up on the jazz fascism, and listen to his horn, they'd hear that the man is still blowing. And more power to him.

- Bill Milkowski; Downbeat; January 7, 1987

Review of Miles CD Reissues - 1990

It's not surprising the Miles Davis receives the lion's share of releases. Chronologically, Sketches Of Spain (Columbia CK 40578, 41:24) is first, and sound-wise, the best. The textures of Gil Evans' difficult writing are clearer then ever before, as inner voices and subtle details blossom and cohere. Miles is moving, Gil is masterful. 'Nuff said. Unfortunately, Kind Of Blue (Columbia CK 40579, 45:10) doesn't fair as well. So What kicks off with a fuzzy, echoey ensemble, Jimmy Cobb's drums are over-enhanced, and Bill Evans' piano takes on an almost-electronic reverberance at times. But Miles is front-and-center, the ear gradually grows accustomed to the sonic vagaries, and the powerful music shines through.

As Teo Macero has related in various interviews, all of Miles' post-'69 music was spliced together from various studio takes. The seams show especially on In A Silent Way (Columbia CK 40580, 38:02), as the sound emphasizes the textural transparency by boosting the high-end dynamic spectrum—the interaction of the three keyboards, John McLaughlin's guitar “comping,” and Tony Williams' hi-hat on Shhh/Peaceful is remarkably lucid, and Miles trumpet obtains a new sheen, but the music now sounds tame. Especially when compared to the bubbling cauldron of Bitches Brew (Columbia G2K 40577, 47:02/46:55). Unfortunately, there's no significant improvement from the original LPs, and some audible pre-echo on Sanctuary has crept into the mix. The session must have been an engineer's nightmare; nevertheless, this first plunge into Miles' most audacious period of experimentation remains an ungainly, exciting, still surprising experience—not the least for McLaughlin's uncliched, ear-opening guitar.

Meanwhile, Miles' early-'50s acoustic groups are among the highlights of the 10 compilations in the 60+ series from Fantasy. The artists are the creme of the Riverside/Prestige catalog, but producer Ed Michel has—for better of for worse—avoided a Greatest Hits series, prefering [sic] to mix-and-match performances with an eye for variety and surprise. This leads to some enlightening—and some dubious—programs. Sound quality varies slightly from disc to disc but is more than acceptable throughout—and revelatory in a few cases. The playing time, in excess of 60 minutes, is generous.

Miles Davis And The Jazz Giants (Prestige FCD 60-015, 68:45), as mentioned above feature more bop than pop, and cuts off in '56 with no samples of the “classic quintet.” (Presumably these will be released complete.) The intimacy of Miles' musings in caught marvelously here.

- Downbeat; 1990